This article is part of a series on compensation for startups. It covers designing and implementing a performance management system. The four parts are:

If you are actively designing and implementing any of these systems, we also have some Do-It-Yourself packages you can buy that include a recording of us explaining all of this in more depth as well as dozens of templates. You’re also welcome to reach out to hello@andthen.com with questions.

For early-stage startups, there’s this constant tension between too much process and too little process. Performance review cycles are especially tricky because they’re a huge time suck for the whole company. All employees direct their attention to writing peer reviews at the same time, 1–2 times per year — it’s like a giant black hole for everyone’s energy.

My friend at Facebook who worked in IT once told me they measured the whole org’s productivity (emails sent, tasks closed, etc.) during the annual performance cycle. This was when the company had about 40,000 employees. They found that even though people could technically work on other things during those weeks, productivity dropped to near 0%.

Founders often ask me if perf cycles are valuable enough for this sacrifice. They wonder whether they should have a system for ongoing feedback instead, so people don’t get feedback just twice per year.

After designing or running perf at dozens of companies, from 5 to 5,000 employees, I’ve come to believe that, yes, perf cycles are an amazing use of company time — if you are ruthless about keeping them short.

Don’t get me wrong, you should definitely give feedback year-round. That’s great. But perf cycles are about so much more than that — especially if you pair all compensation changes with your perf cycle timing. Proper perf cycles force you to look at the whole company 1–2x per year to make sure you’re (1) consistent about things like expectations for employees and the definition of high performance, (2) compensating employees based on the same standards, (3) rewarding high performers, and (4) using your payroll budget wisely (one of the largest company expenses you’ll have). Doing these cycles lets you condense those efforts into a few pre-scheduled weeks so everyone can focus on other things the rest of the year.

In this post, I’ll share my performance review system, which aims to minimize the energy drain while getting those benefits. I’ll outline the steps, tools, and timelines that you’ll need to set up peer review cycles, calibrate reviews, and calculate salary/equity raises.

There are one million debates about the right way to do perf, but most startups need to focus on the basics. My system is a simplified version of Facebook’s and Google’s, which frankly means it’s “old school.” But it will get the job done and scale for a long time — up to thousands of employees. If you’re a small startup, I recommend rolling this system out by the time you have 50 employees.

Perf system in the broader context

This perf system goes hand-in-hand with two other systems: leveling and compensation. These three systems work together to let you pay for performance, which is something I deeply believe in. The results of a perf cycle drive an employee’s salary raises, title/level growth, and other compensation changes.

Before setting up perf, you’ll want to set up the other systems.

Design your leveling system.

Design your compensation philosophy.

And then rollout your compensation system in tandem with this performance cycle.

Many HR leaders don’t believe in performance ratings, but for pay-for-performance to work, you need them — and you need them to be numerical so you can plug them into compensation formulas. This helps you be consistent across departments when you make comp and level changes.

In my system, each perf cycle produces two numerical outputs for every employee:

a performance rating — a number

a promotion decision — a binary Yes/No

Those two outputs go into a compensation spreadsheet, and it spits out salary and equity multipliers for each employee. That’s the basis of the formulaic compensation model.

Core principles of my perf design

These are my strongly held beliefs that guide the design of this performance review system:

Who: Everyone all at once

For fairness and consistency, I review the whole company at the same time, not in separate groups. I’ve seen systems based on start date — you get a review on your 1-year anniversary — but this introduces bias and a bunch of complexity. Rolling systems tend to mean that different standards are applied to different people as circumstances change month to month.

Execution Speed: Fast

This process can go on forever if you let it. Get it done (painfully fast) and move on.

How: Comp and perf at the same time

To tie performance to compensation, you need them to happen in the same time period.

How often: Twice a year

Once per year is too infrequent for how fast our industry moves, but quarterly is overkill. I do a heavy cycle and a light cycle, as outlined below.

Here’s what my typical 2x per year perf schedule looks like. In January, I do a full performance review and an all-company compensation review. In June & July, I do another full performance cycle, and comp changes, but only for promotions and tenure-related adjustments. But you can decide on the months that work for you.

Without further ado, let’s get into designing and rolling out your perf system.

This article has two parts:

A) How to prepare (aka what you need before you start)

B) The 5 steps of the performance process

A. Prepare to roll out your performance management system

To run a perf cycle, you need to set up the following foundation.

Technology

Use a tool to collect peer reviews — Lattice and Culture Amp are great. Everything else can be done in Google docs/sheets until you are working with hundreds of employees.

It takes time to set tools up, so make sure you’ve chosen one and uploaded your organizational data before you start the perf cycle. If you’re already using a human resources information system (HRIS), make sure it accurately reflects which employees report to which managers. There is usually a subset of people who switched managers during the perf cycle, so you’ll need to chase down who “owns” the review for those employees.

Budget expectations

Before you start an annual perf cycle that is tied to a company-wide comp adjustment (typically the January cycle), set expectations with managers and leadership about whether you’ll be giving raises this year and how big/small they’ll be. This is a significant financial decision, so sit down with your finance team and model how much your overall payroll budget can grow for the next year.

In the past, the average was 4%–7% payroll budget growth per year and everyone expected raises of 3%–5% or more. Now, the average payroll growth budget is more like 0%–3%. We saw a lot of 1%, 0%, and layoffs in the slowdown of 2022 and 2023.

Eligibility criteria and salary change effective date

Set guidelines for which employees will participate in your next review cycle. Usually, employees who started at the company 2–3 months before the start of the perf cycle can participate (for example, October 1 if your cycle starts on December 15). There’s always some employee that started on the day or the day after and people CARE about being included, so be conscious of who is close to the cutoff.

Decide what you’ll do with people who were on a leave of absence like parental leave or medical leave. Often companies just give those folks a “meets all” or average rating for the time they were out.

The final thing you need to do is decide when salary changes will take effect. Talk to your finance/payroll team about what makes this easiest operationally but it’s usually either the 1st or the 15th of the month that you plan to deliver compensation letters.

Timeline

My company-facing timeline is typically 6–8 weeks per perf cycle.

You need to budget an extra 4 weeks for the HR team to prepare, especially for the cycles with a market-based comp review. It takes time to get market data, benchmark against today’s comp, figure out which managers are reviewing which employees, and make sure the HRIS is updated. The HR timeline is usually 3 months in total.

The most important thing you can optimize in your timeline is the peer review step, when all employees are engaged. THIS is the “danger zone,” when your company's productivity will screech to a halt. So make the peer review step as short as possible. I usually go for 7 days or 10 at the most — which is 2 weeks with 1 weekend in between. It includes both (1) reviewer selection and (2) writing. Some companies block 1 day and throw a party for everyone to only write perf reviews (we did this at CZI and someone before that had done it at Quora) with a goal of getting it done as fast as possible. Just don’t let it drag out for weeks.

The 6–8 week timeline breakdown

A few days for kickoff: 1 training for managers, a company-wide kickoff email, and 1 training for all employees (in that order)

Up to 10 business days for peer reviews, which includes peer reviewer selection and writing reviews for all employees

2 days for peer reviewer selection

1 day for managers/HR to approve peer reviewers

Up to 7 days for writing reviews

2 weeks for manager to submit ratings/promotion recommendations and calibration meetings [managers & HR only]

1 week to calculate compensation based on the final ratings and promotion decisions and to prepare comp letters [HR only] (this is also a good week to do a second training for managers on comp/delivering reviews)

2 weeks to deliver reviews and comp letters to employees in 1:1s [managers]

If you’re starting from scratch and designing your first performance review system, along with leveling and compensation, budget at least 3 months from start to finish:

8+ weeks to design your perf, leveling, and comp systems, then re-level all current employees

6–8 weeks for your first perf cycle

Communications

To prevent one-off issues during perf cycles, and to help people meet deadlines, plan out a thorough communication cadence in advance. Design one sequence for managers (weekly) and one for all employees (less frequent).

If you do nothing else, be great at communicating to managers, because employees will go to them with questions. Make sure managers understand the process and feel ownership over the perf cycle so they can lead their employees through it.

A typical comms cadence consists of email drumbeats, all-day calendar invites silently placed to remind people of deadlines, and trainings for managers and employees. If you’d like to see my team’s super detailed timeline of the day-to-day and week-to-week perf communications, feel free to buy our DIY package for Performance Reviews..

Ratings and language

The next set of decisions you need to make is around ratings. Ratings let you talk about people’s performance and bucket them into groups for that perf cycle, even across a wide variety of departments and role types so you can calibrate the whole company together. As I mentioned at the beginning, ratings also eventually turn into compensation multipliers to tie performance and compensation together.

First, choose your numbers. Most companies have 5 or 7 ratings. Facebook had 7, with 4 at the middle (average). As far as I know, there’s still an ongoing debate at Meta about 5 vs. 7 points. The more ratings you have, the more granularity you get. For a 0- to 200-person startup, I prefer 5, but I’ve used both. Just pick one.

You are welcome to have more. For a while, Google had hundreds of ratings. It creates more of a stack rank, but it does sort of end up with a lot of arbitrary conversations about the difference between a 3.65 and a 3.64.

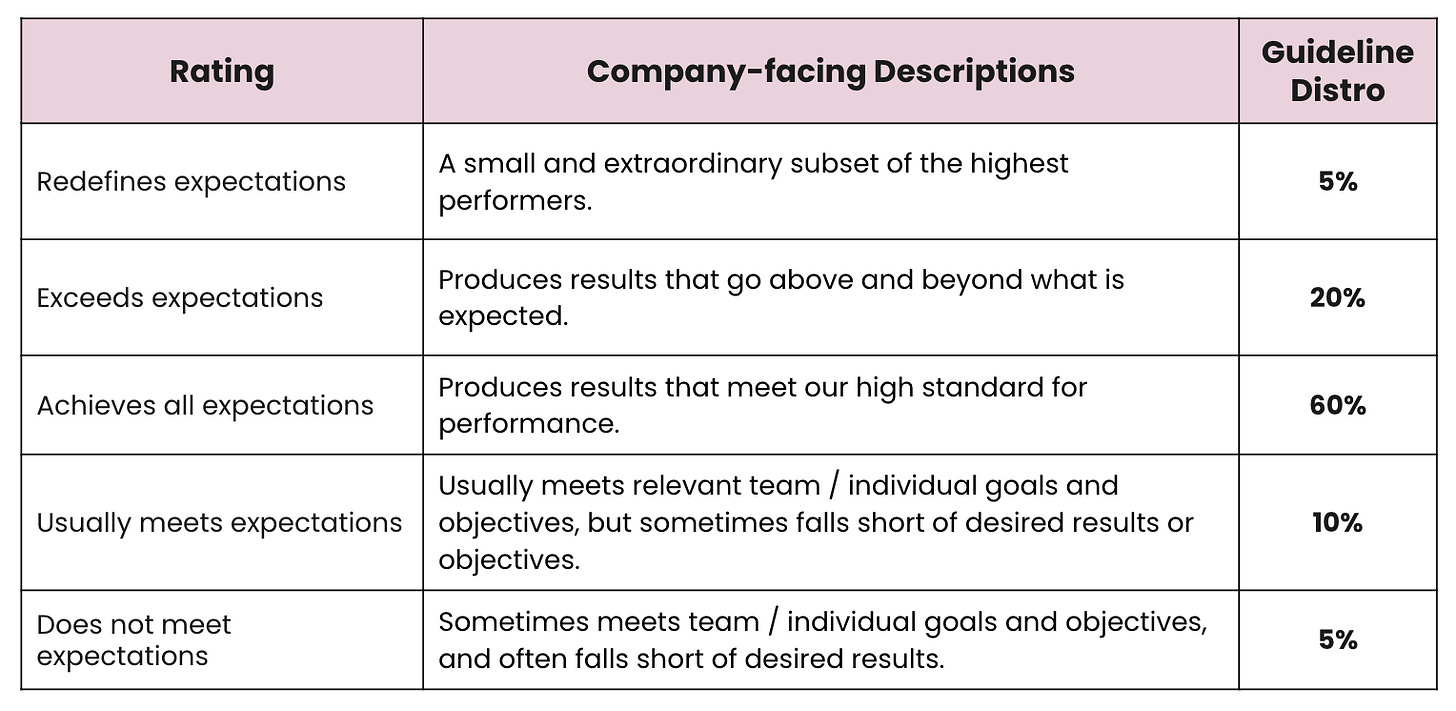

Once you have your number, name the ratings — for example, in a 5-point scale, a 5 might be “Redefines expectations” whereas a 3 (middle) is “Meets expectations.” (Among other reasons, a rating name can prevent confusion in calibration, because in the leveling system I use, each level is also a number.)

Lastly, write language to describe each rating. This helps managers and employees understand what each one means. I usually use this language in compensation letters that are given to employees as well as in manager trainings and other comms.

An example of all of this is below in the next section.

Distribution curve and guidelines

I recommend publishing a suggested distribution curve to managers and employees, to help set expectations about how many people will get each rating (what % of employees).

It’s important to say this is NOT a forced curve. Microsoft used to have a forced ranking system that led to consistently firing the bottom 10%; they’ve since retired this. People have a lot of PTSD about forced curves.

Instead, the purpose of the guideline distribution is to (1) educate and reinforce the meaning of each rating and (2) provoke conversations during calibration.

Managers tend to inflate their ratings, so a guideline distribution helps shine a spotlight on that and guide calibration discussions. If a whole team is much higher than the guideline, then it prompts us to discuss why and whether that team is truly performing above the rest of the company. Maybe they are, but often they aren’t and these ratings were just given by a manager who is newer or struggles with hard conversations so they want everyone to be above average.

Any rating guidelines I publish to managers are intended to promote discussion rather than enforce hard rules. I’m a fan of publishing the guidelines to employees as well and explaining them. To give you more detail, here is a template doc that shows examples of rating guidelines and how they could be communicated to managers.

Once you’ve made all the decisions above and gotten organized, you’re ready to begin your performance cycle.

B. The 5 steps of a performance review cycle

Every cycle goes through this arc:

Kick off and collect data from employees through self-assessments, peer reviews, and upward reviews

Managers make rating and promotion recommendations

Managers and leadership calibrate the recommendations across the company

HR adjusts compensation based on performance

Managers and HR deliver reviews and compensation letters

1. Kick off and collect self-assessments, peer reviews, and upward reviews

This step is the #1 time sink for your company because all employees will be involved. Lighten their burden by making trainings and peer reviews light and efficient — while still collecting enough data to inform the manager’s rating recommendations.

Trainings

To kick off, schedule a manager training about one week before peer reviews begins. Cover the perf timeline, ratings scale, distribution curve, and how to make rating and promotion recommendations.

Then, hold a 1-hour live training for employees so they know what to expect from the whole cycle. Highlight what they don’t need to focus on (to help them save time). Explain how perf benefits everyone as a driver of consistent standards and formulaic compensation changes across the company.

Peer selection

Next comes about 2 days for peer selection: 1 day for people to pick their 3–5 peer reviewers and 1 day for managers to approve them.

Make sure employees know to select a mix of peers, cross-functional partners, and direct reports. Look out for anyone being asked to write more than 3–5 peer reviews and have them decline some — for most people, it’s exhausting to write more than 5.

Managers also need to select their own reviewers, which is usually a mix of cross-functional counterparts and direct reports providing upward feedback.

Writing reviews

I recommend limiting this phase to 7 business days or shorter if possible because again, it’s the productivity black hole.

Create a template with questions for reviewers to follow. Avoid a fancy template with lots of questions. I just want to know what someone’s great at and the best things that they’ve done recently.

Four questions are usually enough:

What is the best thing this person accomplished in the last six months?

What are this person’s two greatest strengths?

What are two things this person can do or change to be more effective?

Anything else? (This can be a helpful question to add if it’s private to the person’s manager. It will let people vent frustrations if they need to.)

2. Managers make rating and promotion recommendations

Next, managers read the peer feedback for each employee, consider their experience and results, and make two recommendations for each employee:

a rating (e.g., from 1–5 if you have a 5-point scale)

a promotion nomination

HR should send managers a spreadsheet where they can enter these recommendations. I also send managers the leveling matrix and a guide to calibration that includes the suggested distribution curve and any other guidelines for how to think about ratings and promo nominations.

We typically have managers submit their ratings and promo recommendations in the same spreadsheet that we use for calibration. There’s a template of this in our DIY package.

3. Managers and leadership calibrate recommendations

Even though it is time-consuming, calibration is my favorite part of the performance cycle because I find it invaluable.

Calibration is a set of meetings (among leadership, managers, and HR) to discuss the rating and promo recommendations. You talk about each employee’s performance and use the discussion to ensure that managers are using the same criteria for things like expectations at each level or for what good/great performance looks like. During calibration, you should change rating/promo nominations as needed.

The result of all of these meetings is a final set of ratings and promo nominations for every employee. Ideally, it is also a robust discussion that deepens the understanding between all your managers about expectations and performance at your company.

I’ve tried a zillion times to cut down on calibration meetings by moving them to async or a tool. There is undoubtedly a way to do this asynchronously, but I find the in-person discussion to be one of the best uses of time all year.

Start by calibrating with managers

The first calibration meetings are at the department level.

In a very small company, it’s possible to calibrate many departments with just one meeting. (You can typically calibrate about 20 people in 2 hours — 5 minutes per person, plus some buffer.)

But once departments have more than 5–8 people, you’ll want to break it into multiple meetings. It’s valuable to have adjacent departments calibrate together if they work closely (like eng and product) or have similar types of roles.

In a 50ish-person org, I would suggest doing:

an EPD calibration

a “business” or “non-tech” calibration

an exec calibration

In each calibration session, you’ll have all relevant managers along with HR and the department’s VP. Start by calibrating all Level 1s in that organization, then Level 2s, and so on. As you move up, managers leave the room when their level gets calibrated.

There are templates in our DIY package to help map out who should be in the room, how long these meetings will last, and the behind-the-scenes agenda for the people team running the meeting.

Before and after: Signs of a good calibration

You’ll know you’re doing calibration right if:

Managers who are easy graders get exposed and adjust their ratings down

Lower performers are found hiding in the “average” rating

A few people who were missing from the promo list are uncovered

A lot of promotion nominations are switched to “no” because they’re not yet ready

There’s a LOT of alignment discussion around expectations (e.g., “what a level 4/5/6 actually is”)

In the before/after of calibration, you’ll often see the entire company’s ratings distribution curve shift down a bit. It often looks like this:

Tips for faster calibration meetings

Send managers a guide to calibration beforehand — here’s a template.

It’s helpful to have a facilitator, note-taker, and timekeeper. HR typically owns the meetings, with heavy support from the main leader of each department.

For time reasons, have people only speak if they disagree (agreement can be a thumbs up).

Calibrations are critical, so you really want to make sure the right managers are in the room. There’s nothing worse than missing someone, so check and double-check. Book meetings far in advance to prevent vacation conflicts.

End with leadership calibration

Once department-level calibrations are done, have a company-wide calibration meeting between HR, the CEO, and the leadership team to finalize recommendations for all employees.

There are four key agenda items in a leadership calibration meeting:

Look at data for the whole company: % distribution for ratings, % promoted, promotion by demographic, and ratings by demographic. Check for patterns. Are technical teams grading harder than non-tech? Are you promoting more men than women or vice versa?

Review outliers: Look at the people who got the highest performance ratings, the lowest performance ratings, and promotions — mostly a “does anyone have questions or concerns about anyone on these lists?”

Calibrate directors and VPs: This is the majority of the time.

Calibrate C-level executives: This is done by the COO and the CEO.

**Make sure managers know not to communicate any decisions around ratings, promotions, and compensation until they are finalized in a compensation letter that they’ll receive AFTER the leadership calibration.**

4. Adjust compensation based on performance

After calibrations are done, you have final rating and promo decisions for each employee. Those decisions can then formulaically calculate salary/equity changes for the following year.

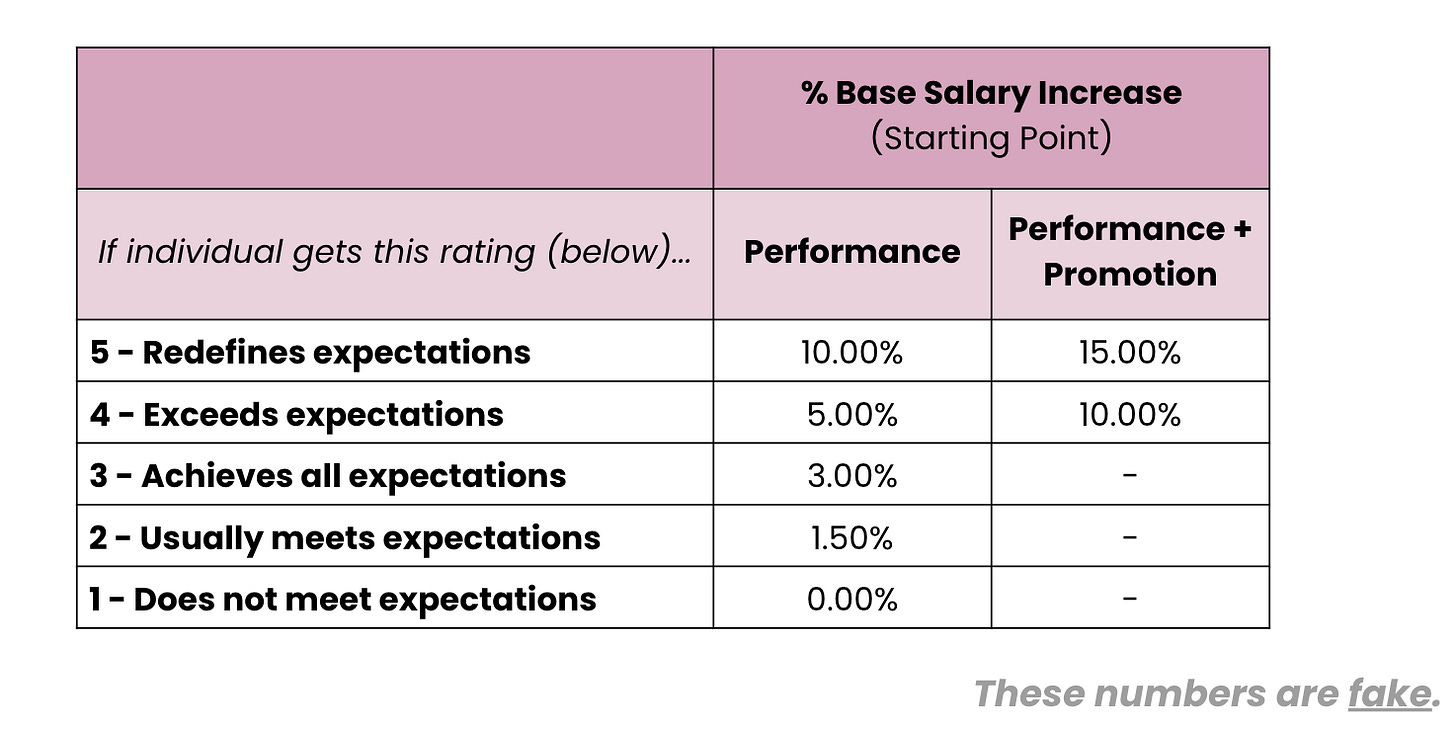

Each rating should be translated into a % increase (multiplier) for salary and equity.

Here’s an example. Please remember that this is fake sample data. Your comp philosophy will inform your multipliers, and your annual budget may change them from year to year.

In this example, an IC making $100k a year who receives a “5-Redefines expectations” but no promotion will get a 10% salary increase — a 1.10 multiplier for a $110k salary next year. (Again, this is fake data. Don’t use it for your company or any salary negotiations.)

Budget adjustments: Before calibration, you can create a draft budget with these multipliers, your guideline distribution curve, and your expected promotion %. Once you have the post-calibration results, you’ll plug them in and calculate everyone’s raises. Compare how much all salaries will cost against your budget. If you’re over budget, you’ll need to decrease your raise percentages, put caps on salary increases, etc.

5. Deliver reviews and compensation letters

After raises have been calculated and finalized, HR creates a compensation letter for each employee that summarizes their perf rating, promotion recommendation, and compensation changes.

Managers receive these letters and deliver them to their employees in 1:1 conversations. To reiterate, make sure managers know not to communicate any decisions around ratings, promotions, and compensation until they are finalized in a compensation letter that they’ll receive AFTER the leadership calibration.

I like to hold a second manager training on the compensation system and how to deliver reviews, because managers need to be prepared for questions and own the decisions. The better you train your managers, the fewer major issues you will have after the managers deliver their reviews. I have never gotten through a performance cycle without a few issues, but manager training is key to keeping that number low.

You can also hold a second training for ICs where you present the formulaic design of your compensation system and how performance and compensation tie together. I almost always do this because it’s a great way to give managers some cover and help prevent discontent in the final 1:1 meetings. Again, there will always be issues, and whole company trainings on compensation often lead to spicy Q&As, but it is still better to support your managers than to leave them to deal with it.

Ok! Once you get through delivering all the reviews and dealing with any aftermath, what you have left is HR cleanup: recording all the changes in your HRIS, ensuring that the new payroll amounts are inputted, and storing the notes from your calibrations somewhere so that you can look at them before the next cycle.

So, that’s the overview of my perf system. If you do nothing else, fight for a short schedule and lightweight peer reviews.

It’s hard enough to extract the necessary data from all employees and make sure all managers are involved in the calibration conversations. Extra frills have diminishing returns and can hurt productivity by extending the timeline. While the time invested in calibration and doing this whole thing consistently is invaluable, it will also slow down your work on other stuff. So get it done — and get back to building.

This article is part of a series on compensation for startups. It covers designing and implementing a performance management system. The four parts are:

If you are actively designing and implementing any of these systems, we also have some Do-It-Yourself packages you can buy that include a recording of us explaining all of this in more depth as well as dozens of templates. You’re also welcome to reach out to hello@andthen.com with questions.

Hi! Love this! Question for you. IAre people only eligible 1x year for promos but can get a promo during either of the cycles or are they eligible for a promo every 6 mos? How would you slot a bonus into this cycle?